Music and Imagination

Invitation and Introduction

If you love any kind of music – classical, romantic, country, metal, ragas, gamelan – whatever genre from wherever in the world, you might be frustrated by the first sections of this post. I’m going “physics” about it for a little while and it might seem to rob it from it’s stimulating mysticism. But it won’t. I promise. So, I humbly urge you to be patient with me for a couple of rows and read on.

This is about one of the great “wonders” of the universe: Our human ability to create music out of the physical reality around us. It doesn’t degrade the cultural and spiritual aspects – nor the bare feeling – of it. Rather, it hails it. And it gratefully acknowledges the opportunity it gives us not only to play, dance, sing, laugh and cry – but also ponder, comprehend and increase the resolution of our minds and souls.

Music, to me, I confess, is what fills in the gaps of our understanding of the universe. Patiently stimulating us to take the next step of growth. It invites us to develop. From our feet to the top of our heads and all that is in between.

And the most important part of it… is you! All meanings counted.

If a tree falls in a forest…

…and no one is around to hear it, does it make a sound?

That is an old thought experiment (well known to some of you I’m sure)

Answer is: Yes and no.

A proper response to this philosphical question lies in how you chose to define what a sound is.

Of course. It might feel a bit too obvious, a sophomore level discussion, but the actual reality of it can be a bit awkward to truly fathom. Not necessarily because its hard, but rather because we’re unaccustomed to imagine what it really means.

At the end of this post I will also kick the issue a bit further to claim it has a great deal of relevance for the survival of civilisation.

Here we go.

What is sound?

Part 1 – Physics

Physically a sound is a series of pressure differences moving through a medium. Waves. The medium is, most commonly (but not necessarily) air. The air molecules, a gas mix of 78% nitrogen and 21% oxygen. The 1% left is mostly so called noble gases. Carbondioxide (albeit not a noble gas) is in there too, but is only 0.042% of the total. If someone or something pushes (quickly) on this mix (air) it will be momentarily compressed at the point of the push. A pressure difference will occur at this point and from there it will propagate on through the air as a wave. The form of this air wave is longitudinal. That is, it wiggles in the same direction it propagates.

If you own a slinky (or at least know what it is) you can create longitudinal waves yourself by pushing it (not waving it). You can experience (see and feel) how a region of higher density (more slinky material per unit of length) moves from one end to the other. A wave in air is much similar. It might be illustrated like this:

The denser regions, also highlighted in red, are caused by something pushing at the air. It becomes a chain reaction where the wave of air also pushes itself, to and fro, until, finally, the energy in the wave dissipates. (You experience this dissipation more or less all the time when you hear a sound that “dies out”.) The energy in the wave does not disappear though. It transforms into another form of energy. The ordered movement of molecules gets gradually more chaotic (due to them colliding) and this mess of molecular movement is no longer, by any defintion sound. (It’s heat. But that’s another essay).

At a first glance it might look like the small dots (illustrating the air molecules) travels. They don’t. They wiggle to and fro as illustrated by the red dots here:

What travels though, is the energy in the push. The consequence of the push that is. The difference caused by the energy. And this is what a wave actually is – a traveling difference. A difference that, on arrival at any point causes an event at that very point.

Before we proceed to what sound might be, let’s just have a look at some other wave forms that might feel more familiar.

A transverse wave occurs perpendicular to the direction the wave propagates. This illustration shows what many think of when waves are the topic. The physics behind is the same. What decides the wave form is the way it is induced and/or the nature of the medium. If you grab your slinky again, and wave it instead of pushing it, the wave form will be transverse instead of longitudinal.

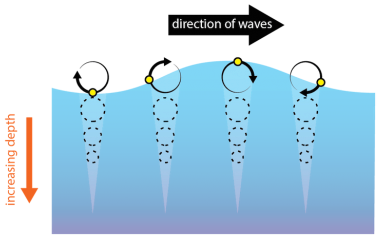

A water wave is a blend of longitudinal and transverse movement. The result is a circular wave form.

That is, the water molecules move in a circular movement up and down (not to be confused with the circles of propagation caused by and impact, for instance a stone thrown in a pond)

Ok. Now armed with som basic insight in wave physics, can we answer the question above?

Well, regardless if you are in the woods with the falling tree or not, the physical phenomena of a wave in air will occur there. The snapping of wood fibre will create lots of pushes on the air causing thousands and thousands of air waves blending into a very complex pattern of wiggles in the air as they travel outward from the event of the fall.

Settled then? Not entirely.

Phenomenology

The other part of this is about what happens when this pattern hits an eardrum. If there is an eardrum to be hit that is. The pattern of wiggles in the air makes the eardrum vibrate in the very same pattern it arrives. The movement of the eardrum causes a sensation (not the kind of “sensation” the mainstream media writes about to sell stuff, but sensation in terms of biophysics). A sensation here is an event where a (to some extent complex) living creature registers its surroudnings via its senses (i.e. the term sensation)) An electrical signal then moves from the ear into the brain where it is perceptualized.

A perception (from Latin perceptio ‘gathering, receiving’) is “the organization, identification, and interpretation of sensory information in order to represent and understand the presented information or environment.[2]” and further “perception is not only the passive receipt of these signals, but it is also shaped by the recipient’s learning, memory, expectation, and attention.[4][5] “

That is, without a receiving perceiver, there is no experience of sound. Or simpler: No sound.

So here goes the harder-to-fathom reality mentioned above:

Without you, the storm in the forest is completely silent.

Now imagine this: Screaming +40 m/s winds hammering the woods. Trunks cracking. Trees falling. Debree flying through the air … and not a sound.

That is, the sounds you experience are created by you! They are a part of what the brain does for you to understand the world around you so that you may survive. Over a lifetime a pattern of related experiences is build into cognitive maps with which you navigate the universe around you. Signals arrive at you, your senses receive them. And whatever form of signal it may be – lightwaves, soundwaves, chemical or tactile, they are transformed into electrical signals moving to the brain, where they are perceived. Sorted, put into the context of earlier and present experiences, made meaning of, understood and reacted too. If it is the sound of an attacking predator it gives you the opportunity to flee or fight. Survival. If it is a piece of music it may cause you to laugh, cry or dance, commune and feel a part of a context. A qualities of life catalogue of thoughts and emotions. Some for more obvious practical usage (fleeing the lion) and some for less obvious (but still in essence practical) reasons – like feelings of love for your partner in life when “your melody” is played.

The creator of all this is you! Using your imagination. So what about the quality of the imagination then? Is it fixed or is it due to your inner capabilities?

Imagination

What all this has to do with music?